When you intuitively divide the number of works by the number of persons available, assigning each, and plug another number as utilization rate, you’re on an easy path to classical 20th-century Taylorism[1]. The fact that the majority of modern workplaces rely on knowledge work, doesn’t toss out such instinct as obsolete.

Focus on idle work, not idle workers.[2]

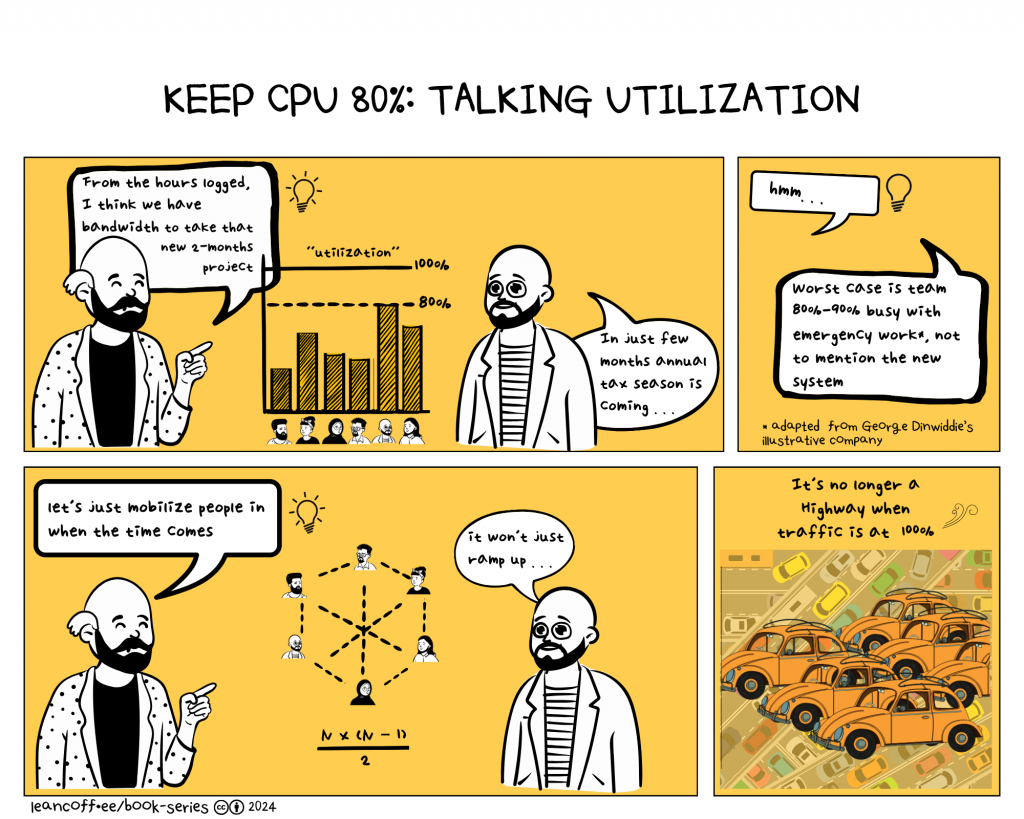

Thinking cycle time is one way to counter such instinct. Poppendieck illustrates having 25 hours cycle time over 80 hours when testing department running at 50% capacity vs at 85%[3]. Instinct will first alarm you that 85% is better than 50%, it won’t directly tell you 80 hours are worse than 25 hours. The latter will put you to rethink utilization rate (against your instinct) to prepare idle bandwidth instead in maintaining cycle time for peak season[4].

- CPU fan spins frantically at 80% load and screens start freezing before your eyes

- Highway at 100% is practically a standstill parking lot.

Picturing that, where do we even borrow the idea that we can ramp up people exactly when capacity is needed?

Even at low capacity, another anti-pattern usually emerges, divide the task still and make one person do more tasks. Achieving high utilization through multitasking (instinct might bravely say as being productive) is instead another layer of bottleneck[5] (despite all individual productivity hacks to multitask that a person is capable of–I know you can). Change (e.g. transformation) is another good reason to build idle capacity, we want to defer executing it until the last responsible moment when facts are closer and options can be locked[3].

Maybe it’s not instinct afterall, but rather a deeply ingrained conception acquired when entering the workplace, validated by the business survival. This is an open invitation to question: at the expense of what?

References

[1] Wikipedia contributors, “Scientific management,” Wikipedia, Aug. 19, 2023. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scientific_management#Criticism_of_rigor

[2] K. S. Rubin, Essential scrum: A Practical Guide to the Most Popular Agile Process. Addison-Wesley Professional, 2012.

[3] M. Poppendieck, T. D. Poppendieck, and T. Poppendieck, Lean Software development: An Agile Toolkit. Addison-Wesley Professional, 2003.

[4] G. Dinwiddie, Software estimation without guessing: Effective Planning in an Imperfect World. Pragmatic Bookshelf, 2019.

[5] M. Cohn, Agile estimating and planning. Pearson Education, 2005.